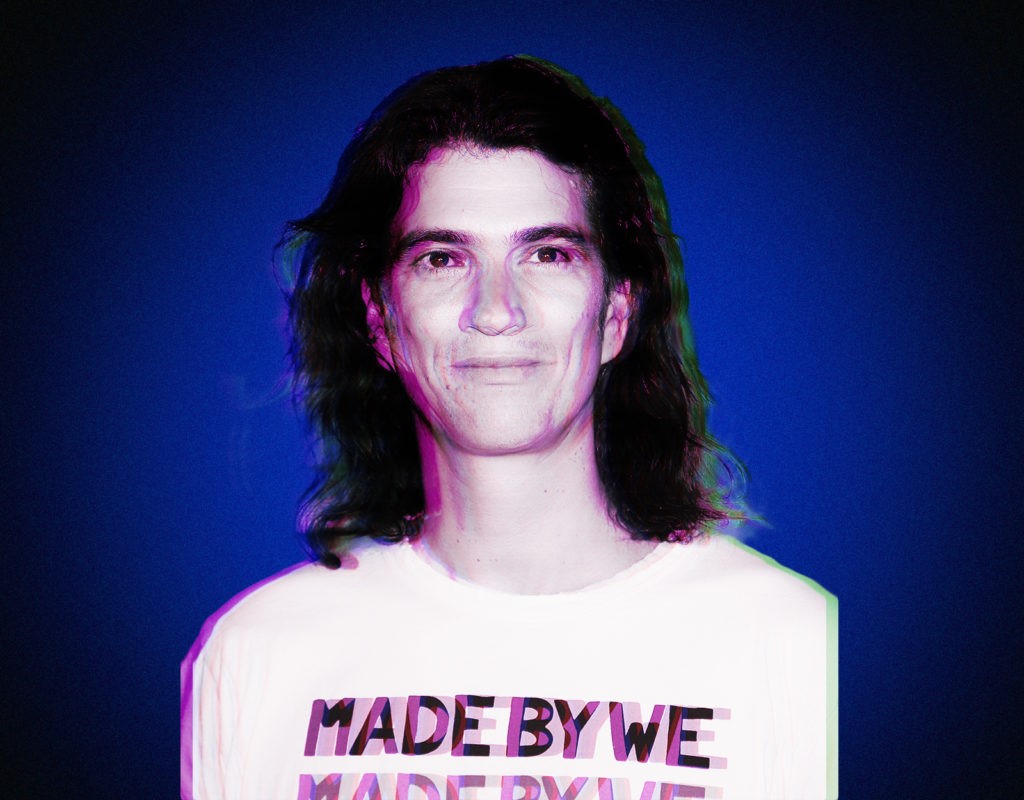

In January, I was given a free one-year membership to WeWork. I had no idea what I was going to do with it, but thought, sure, I’ll sign up and try it out. My first visit was in the new Salesforce tower in San Francisco. As my planned meetings didn’t start until lunch, I thought I would work that morning from the iconic building. I walked there, arriving at 7:15am, only to find out it didn’t open to “hot desk” members until 9am. I did what I’ve done for two decades – found a coffee klatch and got to work. Over a few Americanos, I got to (almost) inbox zero, reviewed work, and completed some presentations. A very productive 90 minutes. But I was anxious to be inside the Salesforce tower, so I hovered my caffeinated husk to 1st and Mission. A short elevator ride got me to the WeWork floor. I stood at the back of a long line of people waiting to check in. As this was my first time, I had to create my account – they took my picture, I wrote an autobiography of wants, needs and hobbies, and gave me my black card. I was now a part of the “physical social network” – how WeWork founder Adam Neumann refers to his empire.

I got free coffee. I was told that I would have to pay for a LaCroix, so I abstained. I then was shown my hot desk, a library quiet setting, with instructions that if I wanted to make calls, I would have to go to one of their super-hip phone booths. I made camp. Within 10 minutes, I needed to make a conference call, so I grabbed my laptop and crammed into the booth and shut the door. But this space wouldn’t support Superman’s changing, let alone a laptop. It was designed for someone who used an iPad mini, and my first thought was that I was too old to really appreciate this. Call ended and I went back to my hot desk. This cycle repeated a few more times in my three hours there. Over that time, the lobby came more alive – ping pong, peer networking, coffee drinking. I felt old, like I hadn’t adapted to the new way of working. This wasn’t how I got work done.

I decided that I would take advantage of my WeWork membership like a coffee shop. My productivity was shot there, so I would be a tourist and get my free coffee and enjoy the lobby buzz for a short respite in whatever city I was in.

And then eight months later, the empire crumbled. Rapidly. Consistently hilarious Scott Galloway started the expose cycle of the bizarre financial valuation when they announced their IPO. And this set off an avalanche of rational minds wondering, WTF? The lead investment firm, Softbank, has dumped nearly $8 billion into it. Now, layoffs are imminent, and the CEO is out, with a handy $1.7 billion parachute. Such malfeasance even gets US Senators conflating WeWork (somehow) with support for socialist candidates. Umm, yeah Senator Cotton, you are making the point of why a Democratic candidate would be beneficial here.

And with all that, the phone booths were recently discovered to have “elevated levels of formaldehyde” and are shortly going to be taken out of service. Great. Not only was my workspace inhumane and unproductive, it was going to cause cancer.

But the biggest lesson that needs to be learned here isn’t the Elizabeth Holmes level lunacy of modern leaders. It is in the future leaders. The new entrepreneurs that embraced the “you-take-care-of-it” simplicity of WeWork’s flexible space leasing. One of the best (and most frustrating) things a startup founder can do is negotiate an office lease. WeWork removes all the legal complexity and negates commitment with its monthly terms. For our next generation of leaders, don’t we want their skin in the game by signing a five-year term? You learn a lot about yourself, your business, and your commitments by going through the office leasing process. Taking that away only serves to exacerbate the can’t-fail, snowflake mentality that swarms the anointed offspring of today’s autocratic leaders. Swinging for the fences requires that you have some pain of failure. Of building future success. Without it, tomorrow’s leaders will have the same authoritarian delusions of grandeur that Adam Neumann had, where he wanted to be “president of the world.”

– James Rice, Digital Experience